Three Ways To Spice Up Your Python Code

I describe some simple methods to improve on your Python codes integrity and durability

Spice Up Your Life Python 🐍

I’m currently working on a side project that I’ve written in Python. Now I’ve have a lot of experience with Python before, I used it primarily to write a load of scripts for automating processes for when Bash didn’t quite cut it. Don’t get me wrong Bash is great, but like for every other language out there, each has its purpose in the world.

My experience with Python didn’t go beyond setting some variables, hitting endpoints, executing some Bash commands to install some vendor components. All of which is what makes Python so great right? Implying on types is useful for some cases. In fact this reminds me of a tweet I saw, I can’t find it again but it went something like this:

Stages of learning programming:

- Learn a typed language, such as Java - complain at its complexity

- Learn an untyped language, such as JavaScript or Python - marvel at its simplicity

- Get frustrated at implied types in step 2

- Revert to step 1

During said experiences I came across some poorly written scripts whiched triggered some pet peeves: what object a function is expecting, or what it returns? Did I break some downstream function? This made it terribly difficult to add new functionality to scripts.

With this side project I wanted to make it right from the start. So I said to myself these are the key areas I want to target:

- The application must be extensively tested (did I mention I love tests?)

- Functions must clearly define what the type of the objects the parameters are, and what the types of the objects they return are.

BestPractices are upheld throughout the way

From this list, we can include the following to solve the above:

Tests

Alright so I know this one is a given. But in all honesty I’ve never really tested Python code before. Why so? I found it difficult to mock API calls and the effort required for the initial learning curve didn’t seem to pay off for the tiny script I was automating. Given the scope of my side project is rather large, this is a great opportunity to learn. Let’s start with a basic function:

# scratch.py

def increment_int_by_one(int_to_inc):

incremented_int = int_to_increment + 1

return incremented_int

While this is something easy enough to test by doing so manually, at some point its functionality may increase, and at that point we would require automated tests to ensure its original feature-set was unchanged.

Implementation

There are several testing frameworks out there, but for my use case I am using the built-in unittest which is easy enough to use. A basic structure of a test file is seen below:

# test_scratch.py

import unittest

import scratch

class TestIncrement(unittest.TestCase):

def test_increment(self):

"""

Should successfully return int value 2

Given a parameter of int value 1

"""

expected = 2

int_to_inc = 1

actual = scratch.increment_int_by_one(int_to_inc)

self.assertEqual(actual, expected)

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

There’s a lot going on here, let’s break it down by section.

Imports

import unittest

import scratch

Here we are specifying the modules that the test file is going to interact with. unittest is the testing framework and scratch is the Python file containing our business logic, as written earlier.

Class Declaration

class TestIncrement(unittest.TestCase):

Simply enough, this is a class that extends the unittest.TestCase class, for which then unittest can then execute all the test methods defined within it, and you can name them like class TestXXXX. There is no limit to how many classes you can have, but I like to group my TestClasses together in terms of what logic they are testing.

Test Methods

def test_increment(self):

"""

Should successfully return int value 2

Given a parameter of int value 1

"""

expected = 2

int_to_inc = 1

actual = scratch.increment_int_by_one(int_to_inc)

self.assertEqual(actual, expected)

These methods are the real juicy bits of your tests. Here you are defining the parameters that are going to be used by your functions, and hitting the logic you are testing. For each test that you write you will alter the test name, description, expected values, and input parameters accordingly to what you are testing.

Main Method Invocation

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

To close off nice and easily, this will tell Python to invoke all test classes that are described within unittest.TestCase.

Execution

Now just execute the test file and it will now run as expected:

> python -m unittest test_scratch

.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.001s

OK

A nice little touch is that we don’t even need to provide -m unittest to the Python intepreter since we have defined the main method invocation:

> python test_scratch.py

.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.002s

OK

Static Type Checking

As I mentioned before, Python is great for throwing together a script to automate some task. It’s quick and easy to do mainly because the type of a variable is implied from whatever you set to it.

>>> my_int_var = 1

>>> type(my_int_var)

<class 'int'>

This also applies to functions that take in a parameter, the type for it is implied from what it receives! Let’s revisit our incrementing function from earlier:

def increment_int_by_one(int_to_inc):

incremented_int = int_to_increment + 1

return incremented_int

>>> print(increment_int_by_one(1))

2

>>> print(increment_int_by_one(100))

101

All good so far. But what happens when we pass in something that is not an int, such as a string?

>>> print(increment_int_by_one("1"))

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in increment_int_by_one

TypeError: must be str, not int

Yikes, that’s a misleading error! Having a look at the error straight away, you’d be confused at ‘what’ must be a string, not an int - didn’t you accidentally provide a str? So why is it telling us it must be a str and not an int?

What this is actually error-ing on is how an int is being concatenated to a str on the left-hand side of the + operator.

Under the hood, Python believe you are trying to do a string concatenation because the parameter is of type string, and is on the left-hand side of the + operator. The below shows a valid way to perform a string concatenation:

"1" + "1" # -> "11"If the int value was on the left-hand side of the operator and you passed a string, you’d get something like this:

>> 1 + "1" Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

But changing the right-side of the operator won’t fix this for us. What we need is to implement typing.

Implementation

Python 3.6 onwards introduced static type checking, so make sure you upgrade to it if you haven’t already - which you might want to do very soon as Python 2 is EOL in 2020!

Taking our above increment_int_by_one function, we can add : int to the parameter which will tell the function what type it expects the parameter to be.

def increment_int_by_one(int_to_inc: int):

incremented_int = int_to_increment + 1

return incremented_int

Now when we pass in a str as the parameter, we still get the same error we saw before. However, if the IDE you are using supports it, you will receive type hints!

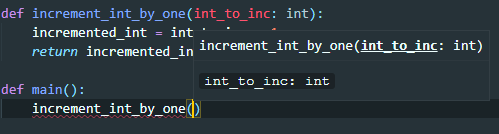

I’m using VSCode with the Python extension installed too, you can see the hint that appears includes the type of the parameter.

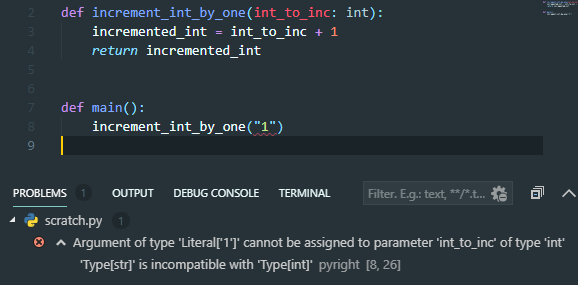

VSCode also has the ability to check the type of the value you are passing into the function:

Here we have a visual indicator that the string is incompatible with the int type of the function. Alongside this, in the Problems tab we have a full explanation on what has gone wrong. This is both provided by the pyright extension which can be found in the VSCode Extensions section.

Return Types

So all of that just describes how typing works for parameters, but how can we specify the return type of a function? That is done easily enough too. Let’s extend on our increment function from earlier.

def increment_int_by_one(int_to_inc: int) -> int:

incremented_int = int_to_inc + 1

return incremented_int

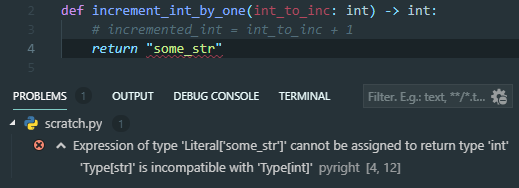

Note the only change here is the -> int which specifies the type it is returning. Now our type checker will highlight to us when we violate this in two scenarios:

The IDE has shown us that the function is expected to return a type different to what it is actually returning…

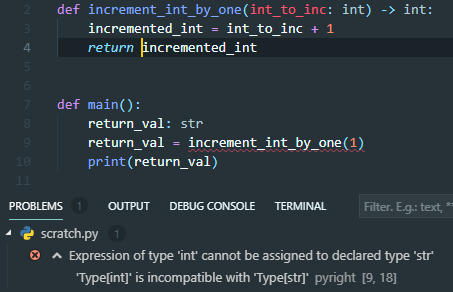

And in this snapshot, we are trying to assign a variable of type str to the output of the function which returns an int!

Another pattern you might see is if a method does not return anything (in Java-speak, it is void), an example of this is if the method is a constructor for a class.

def __init__(self) -> None:

self.attribute = 'DEFAULT_VALUE'

Class Objects

So you might class this (pardon the pun!) as a type of its own, but this is something I’ve learnt all the same recently, so I hope it benefits you too! Python has the ability to construct more complex objects in the form of classes. While I won’t go into the details of that (I’ll leave it up to better resources), I wanted to show how I’ve been able to utilise them.

Test Mocks

One of the main reasons for implementing classes has been to resolve one of my requirements I described earlier on in this post, the ability to test my code easily. For my side project I interface with some third-party APIs to retrieve data, in order for me to test these I need to mock them appropriately. See below for a snippet of the code:

# spotify.py

class SpApi():

client: spotipy.Spotify

def __init__(self, id: str, secret: str) -> None:

ccm = SpotifyClientCredentials(

client_id=id,

client_secret=secret

)

self.client = spotipy.Spotify(client_credentials_manager=ccm)

def get_album_by_id(self, id: str) -> SpAlbum:

return SpAlbum(self.client.album(id))

def query_album_by_title(self, title: str) -> SpQueryRespWrapper:

q = SpQueryBuilder(album=title).build()

return self.execute_query(q)

def query_album_by_title_and_artist(self,

title: str,

artist: str) -> SpQueryRespWrapper:

q = SpQueryBuilder(album=title, album_artist=artist).build()

return self.execute_query(q)

def execute_query(self, q: str) -> SpQueryRespWrapper:

return SpQueryRespWrapper(self.client.search(q=q, type='album'))

You might have guessed it, the API is Spotify’s, and I am using the spotipy library to do the interfacing. The SpApi class is essentially a wrapper around the client to allow me to easily re-use methods across the app. It’s usage would be sp_api = SpApi(), which would return us a client available at sp_api.client. It is this attribute of the class which we want the ability to mock for when we test it. See how I implemented the mock:

# test_spotify.py

import unittest

from unittest.mock import MagicMock

import munch

import spotify

get_album_by_id_response_fname = 'sp_get_album_by_id.json'

with open(get_album_by_id_response_fname, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as f:

get_album_by_id_response = json.load(f)

class TestSpApiClass(unittest.TestCase):

def get_mock_sp_api(self) -> spotify.SpApi:

mock_sp_api = spotify.SpApi('id', 'secret')

mocked_album = MagicMock(return_value=get_album_by_id_response)

mock_sp_api.client = MagicMock(album=mocked_album)

return mock_sp_api

def test_get_album_by_id(self):

"""

Given a request is made to Spotify API for Album ID

Should verify that the API is hit

"""

mock_sp_api = self.get_mock_sp_api()

expected = spotify.SpAlbum(munch.munchify(get_album_by_id_response))

actual = mock_sp_api.get_album_by_id('album_id')

mock_sp_api.client.album.assert_called_once_with('album_id')

self.assertEqual(actual, expected)

Talking about get_mock_sp_api first, this constructs a new SpApi wrapper class, but then it overwrites the client attribute with MagicMocks from the unittest framework. MagicMock essentially creates a mocked object or function for you. When I create a MagicMock with a return_value parameter, it will return that passed parameter when the MagicMock object is invoked.

Did you notice how it specifies the return type too?!

-> spotify.SpApi

The test test_get_album_by_id creates an instance of this mocked Spotify API, so when we call the wrapper method get_album_by_id it makes a downstream call to client.album, which is what we mocked already with the chained MagicMock object! So now we can tell it what to return back when hit with certain parameters - and validating back with assert_called_once_with.

Trying to learn how to implement the above has probably been the biggest blocker for me to test Python code in this way - now that I’ve discovered it I can’t stop using it everywhere!

Complex Object Comparison

Much like the previous section, this relates to the static typing we implemented earlier. I was writing methods that returned complex objects encapsulated in classes, and I wanted to be able to test for equality using unittest’s self.assertEqual(actual, expected).

Let’s take this simple class:

class SomeObject():

some_str: str

some_int: int

def __init__(self, some_str: str, some_int: int) -> None:

self.some_str = some_str

self.some_int = some_int

What we want to achieve is for us to be able to use the below test like so:

class TestObject(unittest.TestCase):

def test_equality(self):

"""

Should successfully test for object equality

Given both objects are equal

When using self.assertEqual

"""

object1 = scratch.SomeObject(some_str='str', some_int=1)

object2 = scratch.SomeObject(some_str='str', some_int=1)

self.assertEqual(object1, object2)

However executing the test gives us an error:

> python test_scratch.py

F

======================================================================

FAIL: test_equality (__main__.TestObject)

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test_scratch.py", line 16, in test_equality

self.assertEqual(object1, object2)

AssertionError: <scratch.SomeObject object at 0x000002A0A0199EB8> != <scratch.SomeObject object at 0x000002A0A0199EF0>

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.003s

FAILED (failures=1)

This fails because we have not overwritten the default __eq__ method on the class. Python then defaults to comparing the memory references for both objects. Since these are two entirely different objects they will be pointing to different memory references. What we need to do is tell Python what defines equality, so let’s add the method onto SomeObject.

def __eq__(self, other):

if type(other) != type(self):

return NotImplemented

return self.some_str == other.some_str \

and self.some_int == other.some_int

And here we are! First we are quickly checking to see the two objects are of the same type before we proceed with the underlying values (fail first, and early!). From there we are checking the attributes within the objects. Hurrah!

One neat little trick I like to do for complex objects that have multiple attributes, is that instead of writing out a new and comparator for every attribute, is to replace it all with this:

def __eq__(self, other):

if type(other) != type(self):

return NotImplemented

return self.__dict__ == other.__dict__

The __dict__ attribute returns the objects in a Python dictionary format, which will contain all the attributes and their values. If the objects are entirely identical then they will return true! Now let’s run the test again.

> python test_scratch.py

.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.001s

OK

Normal service is resumed!!

Closing

I hope the hints detailed in this helped you as much as it did for me! I’m sure there are many more tips out there - as I discover them be sure that I’ll share them once I find them, along with documenting more on the side project I’ve been working on!

Thanks for reading 😃